|

The Shah of Iranaka Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi Americans know something about world affairs. For instance, they know that foreign leaders are only important when they a) attack us, or b) are replaced by someone worse.

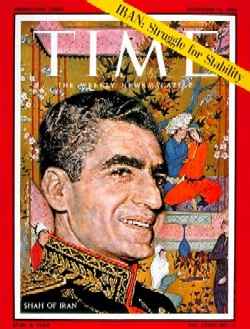

Americans know something about world affairs. For instance, they know that foreign leaders are only important when they a) attack us, or b) are replaced by someone worse. The Shah of Iran falls into the latter category. Americans barely knew what a "Shah" (or an "Iran") was until 1979, when an Islamic revolution ousted the U.S.-loving Shah and replaced him with the U.S.-hating Ayatollah Khomeini. By that point, of course, it was exactly too late to matter. The Shah was king of Iran, descendant of a great dynasty that stretched back one entire generation. His father had seized power in 1921 coup, booted out the British and Russian forces occupying the country and declared himself "the Shah of Iran" in 1925. Unfortunately for the senior Shah, the British and Russians came back in 1941, after accusations that the Shah was a Nazi sympathizer. The old Shah was replaced by his son, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. The early tenure of the new Shah was troubled, beset with insurgency and unrest. The CIA played a major role in solidifying the Shah's regime. Buffeted by internal strife, the Shah was a weak leader who played favorites and blew with the wind.

The reluctant Shah opted for "with you," but the endless dithering had allowed his enemies to consolidate their position, resulting in a coup against his royal authority, followed by a countercoup that reinstalled the monarch. With U.S. support, the Shah stabilized the country during the 1950s and 1960s, importing Western values such as profit-sharing and women's suffrage. But, needless to say, the CIA had not been motivated by altruism. The Shah wasn't just importing decadent Western values from his American and British friends. He was also exporting millions and millions of dollars in oil. The coup emboldened the Shah, and he stepped up to the plate as a ruthless dictator, denying freedom of speech and human rights in the interest of keeping the pipelines open and flowing. Strategically, Iran was an important buffer against the rise of Communism in the Middle East.

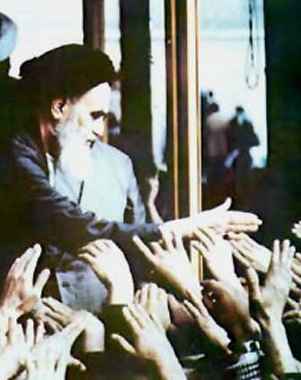

He also developed a repressive intelligence agency, known as SAVAK, which helped keep his increasingly embittered political opponents in line. One of those opponents was the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who became the Shah's deadly enemy after the king allowed government officials to swear their oaths of office on religious books other than the Koran.

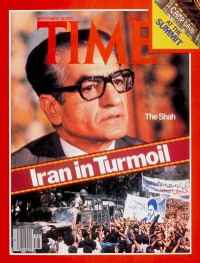

The Shah's government grew increasingly corrupt, as oil revenues flowed to the upper strata of society, leaving exactly the sort of disenchanted underclass that inevitably leads to revolution. At the same time the country began to destabilize in 1978, the Shah was stricken with lymphatic cancer. Even healthy, the Shah had never been a bold and courageous leader. Sick and faced with mounting unrest, he finally lost the country in January 1979. Although he was opposed by a broad coalition of forces, Khomeini's Shi'ite radicals seized power in his wake. The Shah fled into exile. In exile, the Shah traveled to New York, but the Iranians wanted him to come back and face trial. Rather than work the international legal system, Khomeini allowed a student group to seize the U.S. embassy in Tehran, taking seventy hostages. The resulting international crisis lasted for 444 days, directly leading to the fall of then-U.S. President Jimmy Carter and the election of Ronald Reagan.

The Shah himself didn't live to see the chaos that his poor leadership skills engendered. He left the U.S. in an unsuccessful attempt to defuse the hostage crisis and took up his convalescence in Egypt. The cancer finally took him on 27 July 1980. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, another American ally in the region, ordered a state funeral for the Shah and allowed him to be buried in the Rifa'i Mosque in Cairo, sparking a fresh round of protest from Islamic fundamentalists. The grave site is technically designated as "temporary" in lieu of the day when the king's mortal remains can be safely returned to his homeland, currently estimated to be the same time that hell freezes over, give or take a few days.

|

In 1953, British intelligence joined forces with the CIA to bolster the Shah's power as a pro-Western dictator. The king was uneasy about the plot and threatened to back out. The CIA drafted his sister and U.S. Gen. H. Norman Schwartzkopf (father of

In 1953, British intelligence joined forces with the CIA to bolster the Shah's power as a pro-Western dictator. The king was uneasy about the plot and threatened to back out. The CIA drafted his sister and U.S. Gen. H. Norman Schwartzkopf (father of  But the Shah's regime grew increasingly autocratic. Although Iran had a constitution which called for a democratic government, the Shah's reign took on an increasingly imperious tone as he borrowed titles and customs from the Persian Empire of antiquity.

But the Shah's regime grew increasingly autocratic. Although Iran had a constitution which called for a democratic government, the Shah's reign took on an increasingly imperious tone as he borrowed titles and customs from the Persian Empire of antiquity.  Khomeini was a fundamentalist Shi'ite

Khomeini was a fundamentalist Shi'ite  The Shah's ouster also fueled discontent in other countries where tension existed between American-supported monarchs and Islamic fundamentalists, particularly

The Shah's ouster also fueled discontent in other countries where tension existed between American-supported monarchs and Islamic fundamentalists, particularly