|

Star Trek In 1964, a guy named Gene Roddenberry produced just one in a series of failed TV pilots, an episode of something called "Star Trek." It was a flop. The network hated it, especially the guy with the pointy ears...

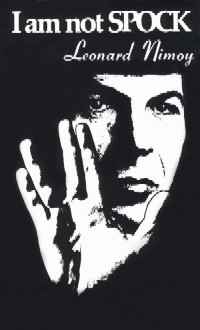

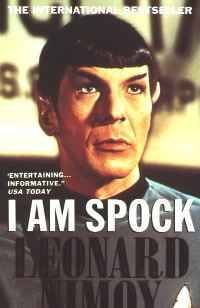

In 1964, a guy named Gene Roddenberry produced just one in a series of failed TV pilots, an episode of something called "Star Trek." It was a flop. The network hated it, especially the guy with the pointy ears... Perhaps just to be polite, they let Roddenberry retool the show. This fateful decision set off a chain of consequences that is directly responsible for the fact that your cellphone now flips open like a clamshell rather than, say, popping out like a switchblade. And they say television isn't important. While the cell phone is the most visible effect "Star Trek" had on our daily lives, it's just one of many. Love it or hate it, "Star Trek" pervades Western Civilization like the Great Plague pervaded the Dark Ages, only with slightly fewer boils. Roddenberry's dopey vision of utopia first hit the airwaves in 1966 with a atrociously bad hour-long story about a hairy sci-fi salt-vampire with the power to shapeshift into the form of a buxom babe in a lame miniskirt. Despite this unfortunate start, the show generated some buzz. While Roddenberry himself vacillated between adolescent egomanic and inspired visionary, his storytelling skills per se were never remarkable. Fortunately, the debut of a the high-profile science fiction show (with then-unprecedented special effects) attracted some of the greatest minds in the genre, from Frederick Pohl to Harlan Ellison. These writers helped craft some of the greatest science fiction on television, tales of time-travel and alien mating rituals and mind-bending parallel universe. Just to even things out, these ground-breaking epics of creative storytelling were interspersed with unwatchable disasters about fascist female aliens stealing brains and heavy-handed Christian allegories. The series made B-list Hollywood stars out of hammy overachiever William Shatner and Leonard "I'm Too Good For This" Nimoy as the lead characters, Capt. James T. Kirk and Mr. Spock, and it made enduring C-list celebrities out of the rest of the cast.

The most notable influence of the original "Star Trek" was on the development of technology. 'Trek debuted just before silicon chips made their explosive arrival in society, and the shape of things to come adapted to reflect the cool gizmos employed by the intrepid crew of the Enterprise. The flip-open communicators used by the characters were a primary influence on cell phone designers, the most obvious example. Anything from a TV to computers showed the influence of Trek, to greater and lesser extents. The show also set the bar for a number of things still in development, from virtual reality to voice-activated computers. Even research by quantum physicists into teleportation, once thought scientifically impossible, has been influenced by Trek tech. Trek also played a strong role in foreshadowing and encouraging social trends, most notably the elevation of women and minorities. The crew of the Enterprise was a remarkably diverse bunch. The bridge crew regularly featured an African-American woman and an Asian man, working as professionals on an equal footing with their white compatriots. Nichelle Nichols, who played ship's communication officer Uhura, was considering quitting midway through the show's run because her character often had little to do, but she was exhorted to stay by Martin Luther King, who felt the character's presence conveyed a powerful message of equality to young people. Later in the series, Nichols and Shatner would take part in the first interracial kiss ever shown on television (albeit one forced on them by alien mind control). Other episodes directly and allegorically addressed heavy social issues of race, gender, sexual mores, reproductive freedom and violence, often with notable success. Naturally all this thoughtful progressiveness baffled the network executives at NBC, who bounced the show around between several different time slots before canceling it ignominiously in the middle of its third season. Instead of being forgotten as so many shows of its generation were, Trek found new life in syndicated reruns, and its popularity grew steadily despite its apparent demise. When Star Wars came out in 1976, the resurgence of interest in sci-fi led to the first Trek movie, which debuted in 1979. Freed from the constraints of network television, "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" allowed Gene Roddenberry to fully realize his vision of what Trek was all about. The result was a charmless two-hour plus movie with a lot of talk and very little action. Despite these flaws, the movie did well enough to inspire a sequel, albeit at a much lower budget level. They didn't let Roddenberry write that one, so it was a smash hit and the franchise was reborn.

ST: TNG began as another Roddenberry-dominated project, which is to say, it sucked. What Roddenberry brought to Trek should not be underestimated the success of the show had everything to do with his vision of a bright and optimistic future in which humanity outgrew the flaws of its current age. It's just that he was a lousy writer. Fortunately, as TNG went on, new blood entered the production team and elevated the show to even greater heights than the original had enjoyed. TNG featured more intelligent stories than the original Trek, and much less campiness. Its seven-year run was incredibly popular and contributed more elements to the cultural lexion, including notably the "holodeck," a virtual reality environment much sought after by socially inept teenagers, and the Borg, a cybernetic monster race whose slogan ("Resistance is futile. You will be assimilated.") became emblematic of such modern-day phenomena as Microsoft. In the 1990s, you couldn't have too much of a good thing. The ratings success led to spinoffs. The first of these was a tremendous show called "Star Trek: Deep Space Nine." It featured complex stories dealing with science and religion, and extraordinary acting and character development, the likes of which had never been seen before on Trek. As surely as night follows day, these qualities led to much weaker ratings than the franchise had recently enjoyed. But DS9 was still the top-rated syndicated show for most of its run. So when Paramount launched its own fledgling television network, it went back to the Star Trek well for a flagship program. By then, Roddenberry had died, and with him died the concepts driving Trek. His replacements were arguably just as bad at writing as he was, except without the whole inspired visionary thing. "Star Trek: Voyager" debuted in 1995, and it was awful. Not awful in the sense of the brain-stealing aliens of the original series, but more in the sense of the numbingly tedious formulaic tripe mentality that won television its reputation as a "vast wasteland." Voyager ground out seven seasons of flavorless gruel under the label of Trek for steadily sinking ratings (despite the addition of a startlingly large-breasted Borg chick named Seven of Nine), while a series of TNG-based movies met with mixed results at the box-office. Roddenberry's heirs within the franchise a "creative" team by the names of Rick Berman and Brannon Braga carefully analyzed the decline and determined conclusively that the problem was everything except their own limitations. Obviously, a new direction was needed.

They also retooled the franchise for its latest installment. The fifth Star Trek series was called "Enterpise," and they notably left "Star Trek" out of the title, to symbolize just how new and exciting it would all be. Repeatedly citing their desire to write something along the lines of "The Sopranos," Berman and Braga couldn't actually get hired on "The Sopranos" so they decided to set their new series 150 years before the first Trek. The rationale (and I swear to God this is true) was that they couldn't do good writing set in the 24th century because people in the 24th century had good diction, and therefore all their dialogue was reminiscent of such worthless hacks as Shakespeare and Dickens.

The future for Star Trek is unclear, but it's probably not as idealistic and optimistic as Gene Roddenberry's vision of a future utopia. With literally billions of dollars in revenues generated by everything from action figures to video games to books to theme parks, there's precious little chance anyone at Paramount will allow Trek to go gentle into that good night while there's still one cent of cash to be wrung from its corpse. Trek might not continue to prosper, but it will almost certainly live long. And with an infinite number of monkeys working on an infinite number of word processors, well, who knows? Maybe it will even be good again someday...

|

It also fed a steady diet of catch-phrases to an allusion-starved public. Even people who have never watched the show have likely used one or more terms that originated with Trek from "Beam me up, Scotty" to "warp speed."

It also fed a steady diet of catch-phrases to an allusion-starved public. Even people who have never watched the show have likely used one or more terms that originated with Trek from "Beam me up, Scotty" to "warp speed." More movies followed, mostly dwelling on how very old the original cast members had become (they were in their 40s hardly decrepit). The solution to this terrible aging problem was to create an all-new Trek set in the 24th century (80 years after the original). "Star Trek: The Next Generation" cleverly eliminated the age problem by featuring a captain who was already older than any of the original cast members. (In all fairness, however, the actor, Patrick Stewart, had aged well

More movies followed, mostly dwelling on how very old the original cast members had become (they were in their 40s hardly decrepit). The solution to this terrible aging problem was to create an all-new Trek set in the 24th century (80 years after the original). "Star Trek: The Next Generation" cleverly eliminated the age problem by featuring a captain who was already older than any of the original cast members. (In all fairness, however, the actor, Patrick Stewart, had aged well  They brought in John Logan, an Oscar-winning screenwriter, to handle the final TNG movie. The result was a nonsensical flop called "Star Trek: Nemesis," the worst-performing Trek movie of all time.

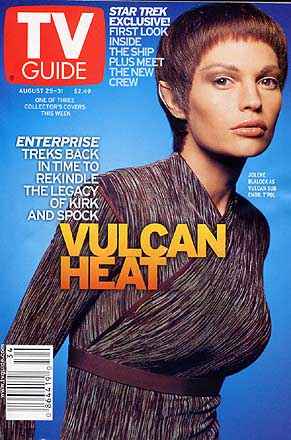

They brought in John Logan, an Oscar-winning screenwriter, to handle the final TNG movie. The result was a nonsensical flop called "Star Trek: Nemesis," the worst-performing Trek movie of all time.  Other radical changes includes having a startlingly large-breasted Vulcan chick instead of a Borg chick, adding a painfully bad Rod Stewart song as the theme, and cleverly creating a post-modernistic vacuum by instilling the show with an utter lack of characterization or plot. Amazingly, the ratings continued to blow chunks and the show was canceled in 2005. When you're not good enough for UPN, that's really saying something.

Other radical changes includes having a startlingly large-breasted Vulcan chick instead of a Borg chick, adding a painfully bad Rod Stewart song as the theme, and cleverly creating a post-modernistic vacuum by instilling the show with an utter lack of characterization or plot. Amazingly, the ratings continued to blow chunks and the show was canceled in 2005. When you're not good enough for UPN, that's really saying something.