What Is The Morning Writing Effect?

Many writers anecdotally report they write best first thing early in the morning, apparently even if they are not morning people. Do they, and why?

1993 notes that many major writers or researchers prioritized writing by making it the first activity of their day, often getting up early in the morning, working only a few hours and then spending the rest of the day on other things. This is based largely on writers anecdotally reporting they write best first thing early in the morning, apparently even if they are not morning people, although there is some additional survey/software-logging evidence of morning writing being effective. Ericsson was wrong about many things, so I wondered how true this was.

I compile all the anecdotes of writers discussing their writing times I have come across thus far. Do they, and why?

Preliminary results from ~400 writers and assorted surveys shows that Ericsson’s trend is, at best, a loose one. Many authors work later in the day, or at night, or claim much longer hours.

Informally, I do observe an intriguing tendency for fiction writers to write early in the morning, and to describe an almost dream-like altered state of consciousness which enables their fiction-writing.

Interviews with writers often touch on their writing process to try to explain how it is done; the hope of the reader is, deep down, to learn how they do the things they do and perhaps the reader can do the same thing. For the most part, the lesson I’ve taken away from such profiles is that every writer is different and there do not seem to be many generalizable practices, if indeed any of them matter (consider how many writers seem to benefit from a stint in jail); for every writer that thrives on writing in longhand with goose quills on parchment, another is unable to think outside a computer text editor, or needs to inhale rotting bananas, or sharpen pencils, or write in a cork-lined room, or insist on a loud phonograph/party for inspiration. (All real examples.)

But in “The Role of Deliberate Practice”, 1993 (among others), Ericsson draws on some anecdotes and particular long-running & somewhat-standardized Paris Review interviews of famous writers to make some interesting points about the relative brevity of most writing sessions (perhaps not too surprising as the physical typing/writing is not the bottleneck) but also the timing of it typically in the morning:

The best data on sustained intellectual activity comes from financially independent authors. While completing a novel famous authors tend to write only for 4 hr during the morning, leaving the rest of the day for rest and recuperation ([Cowley, M. (Ed.). (195966ya). Writers at work: The Paris review interviews.]; [Plimpton, G. (Ed.). (197748ya). Writers at work: The Paris review. Interviews, second series.]). Hence successful authors, who can control their work habits and are motivated to optimize their productivity, limit their most important intellectual activity to a fixed daily amount when working on projects requiring long periods of time to complete…Biographies report that famous scientists such as Charles Darwin, (Erasmus 1888), Pavlov (1949), Hans Selye (1964), and B. F. Skinner (1983) adhered to a rigid daily schedule where the first major activity of each morning involved writing for a couple of hours. In a large questionnaire study of science and engineering faculty, 1986 found that writing on articles occurred most frequently before lunch and that limiting writing sessions to a duration of 1–2 hr was related to higher reported productivity…In this regard, it is particularly interesting to examine the way in which famous authors allocate their time. These authors often retreat when they are ready to write a book and make writing their sole purpose. Almost without exception, they tend to schedule 3–4 hr of writing every morning and to spend the rest of the day on walking, correspondence, napping, and other less demanding activities (1959; 1977).

1984, “Perception and practice of writing for publication by faculty at a doctoral-granting university”

1980, The Psychology of Written Communication: Selected Readings

1977, “Academics and their writing”. London Times Literary Supplement, June 24, p. 782.1

1974, Stimulating Creativity, Volume 1: Individual Procedures. New York: Academic Press.

et al 1970, Creativity

Malcolm Cowley in his introduction (“How Writers Write”) to the first anthology of Paris Review interviews (Writers At Work: The Paris Review Interviews, First Series, ed 1958) summarizes his impressions of the writer’s situation:

…Apparently the hardest problem for almost any writer, whatever his medium, is getting to work in the morning (or in the afternoon, if he is a late riser like Styron, or even at night). Thornton Wilder says, “Many writers have told me that they have built up mnemonic devices to start them off on each day’s writing task. Hemingway once told me he sharpened twenty pencils2; Willa Cather that she read a passage from the Bible—not from piety, she was quick to add, but to get in touch with fine prose; she also regretted that she had formed this habit, for the prose rhythms of 1611414ya were not those she was in search of. My springboard has always been long walks.” Those long walks alone are a fairly common device; Thomas Wolfe would sometimes roam through the streets of Brooklyn all night. Reading the Bible before writing is a much less common practice, and, in spite of Miss Cather’s disclaimer, I suspect that it did involve a touch of piety. Dependent for success on forces partly beyond his control, an author may try to propitiate the unknown powers. I knew one novelist, an agnostic, who said he often got down on his knees started the working day with prayer.

The usual working day is three or four hours. Whether these authors write with pencils, with a pen, or at a typewriter—and—and some do all three in the course of completing a manuscript—an important point seems to be that they all work with their hands; the only exception is Thurber in his sixties. I have often heard said by psychiatrists that writers belong to the “oral type.” The truth seems to be that most of them are manual types. Words are not merely sounds for them, but magical designs that their hands make on paper. “I always think of writing as a physical thing”, Nelson Algren says. “I am an artisan”, Simenon explains. “I need to work with my hands. I would like to carve my novel in a piece of wood.” Hemingway used to have the feeling that his fingers did much of his thinking for him. After an automobile accident in Montana, when the doctors said he might lose the use of his right arm, he was afraid he would have to stop writing. Thurber used to have the sense of thinking with his fingers on the keyboard of a typewriter. When they were working together on their play The Male Animal, Elliott Nugent used to say to him, “Well, Thurber, we’ve got our problem, we’ve got all these people in the living room. What are we going to do with them?” Thurber would answer that he didn’t know and couldn’t tell him until he’d sat down at the typewriter and found out. After his vision became too weak for the typewriter, he wrote very little for a number of years (using black crayon on yellow paper, about twenty scrawled words to the page); then painfully he taught himself to compose stories in his head and dictate them to a stenographer.

Dictation, for most authors, is a craft which, if acquired at all, is learned rather late in life—and I think with a sense of jumping over one step in the process of composition. Instead of giving dictation, many writers seem to themselves to be taking it. “I listen to the voices”, Faulkner once said to me, “and when I’ve put down what the voices say, it’s right. I don’t always like what they say, but I don’t try to change it.” Mauriac says, “During a creative period I write every day; a novel should not be interrupted. When I cease to be carried along, when I no longer feel as though I were taking down dictation, I stop.” Listening as they do to an inner voice that speaks or falls silent as if by caprice, many writers from the beginning have personified the voice as a benign or evil spirit. For Hawthorne it was evil or at least frightening. “The Devil himself always seems to get into my inkstand”, he said in a letter to his publisher, “and I can only exorcise him by pensful at a time.” For Kipling the Daemon that lived in his pen was tyrannical but well-meaning. “When your Daemon is in charge”, he said, “do not try to think consciously. Drift, wait, and obey.”

Other examples include Frank P. Ramsey (“…I wouldn’t have said he worked for more than say four hours a day … he worked in the mornings, probably went for walks in the afternoon, played the gramophone in the evening. Something of that sort.”)

This was interesting to me because I generally do not write in the morning, so knowing that morning is better would be valuable to me, and because it confused me why it would be true. If you are a morning person, you should write in the morning, and vice-versa if you are an evening person. Why would you write when you are miserable? I was especially not a morning person when I was a teenager, and it certainly showed in my first period class at 8:20AM after waking up at 6AM; certainly I never noticed any hidden gift for writing novels manifesting, even when it was a literature class. (Although I did notice a hidden gift for forgetting everything said in those classes.)

Some of the post hoc explanations for why morning might be better make no sense. It is true people are less likely to interrupt you early in the morning; but they are less likely to interrupt you at midnight. It is true people can find time for writing by getting up before their job; but they can sacrifice the same amount of sleep to write by staying up later at night. It is true that the morning might not be a circadian nadir; but that’s not helpful to anyone who is an owl, who by definition is sluggish in the morning, and where does all this energy come from for walking or exercising or partying or researching in the evening, when not writing, if the writer is hopelessly fashed after the vicissitudes of the day? (If the secret of morning writing is merely the nigh-tautological “if you’re a morning person who writes best in the morning, you should write in the morning, and if you’re an evening person, you should write in the evening”, then it’s surely of no value—is there anyone who doesn’t already know whether they are more of a morning or evening person?)

Further, morning writing runs counter to the usual intellectual stereotype of great writers as rising late and being chronometric “night owls”. The “owl” chronotype is usually linked with creativity & intelligence while morning “larks” are considered less creative (but more industrious & favored in many contexts like schools, to the detriment of owls & especially teenagers), so one would expect the opposite: writers to report writing mostly in the evening. (And amusingly, the Wikipedia article on “owls” includes a list of dozens of writers & other creative types while the “lark” article is devoid.) What could be more writerly or bohemian than spending the day researching or enjoying nature or drinking to jazz at the club and then returning to one’s attic in the witching hours to author deathless verse? Nevertheless, great authors routinely rehearse the advantages of living like a farmer and rising with the sun to milk the Muses. (Cal Newport’s Deep Work book points this way, and there is even a writer self-help fad, “The Miracle Morning”, whose central gimmick is getting up early.)

Puzzled, I began noticing in author interviews or writings that when writing times were mentioned, it was indeed more, often than not, partially or entirely in the morning (sometimes disgustingly early like pre-dawn), rather than usually in the evening as expected, and it became startling when I ran into an exception like Ian Fleming or Winston Churchill, who wrote at all in the evening, or Brandon Sanderson or Robert Frost, who work entirely into the wee hours. I am, again, not a morning person but I forced myself up early a few days and skipped my usual email & news-reading routine to focus on writing, and darn if it didn’t seem to work and the writing was worth the price in afternoon circadian slumps. Still couldn’t make myself do it regularly, though.

Causes

Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.

Gustave Flaubert, 18763

If the morning writing effect is real (in the sense that successful writers do disproportionately write in the morning—which is still in doubt given the existing systematic survey evidence is limited to ordinary writers while the elite writers are represented so far purely by haphazardly-selected anecdotes), what is causing it?

One possibility is that there is some sort of ecological fallacy going on: it is possible that, creativity really is higher in owls at night, owls do not improve by writing in the morning, but the best authors are still larks (rather than owls as one would assume from the population-level correlation) and do benefit from writing in the morning (or at least aren’t hurt); and this is because larks have other advantages in becoming the best authors, perhaps related to sheer writing volume & consistent output. No matter how creative it is, an unwritten book is no good. Larks then could write fine at any time and would be overrepresented among the best authors either way, because writing time is confounded with other Conscientiousness-related attributes.

Looking through the anecdotes so far, while it’s true that devotees of “The Miracle Morning” and others frequently claim to not be larks and struggle to reap the benefits of morning writing, the elite writers who happen to write in the morning (currently) do not mention major struggles with getting up early or focusing in the morning, implying that they may well all be larks in the first place!

(Simonton’s “equal-odds rule” suggests that volume of writing output is much more important than it is usually given credit for being, and that writing or research is too random a process to permit sitting down for several years and decide to bang out a beloved masterpiece: one can only try as many things as possible and be surprised when one turns out well, or happens to become a hit.)

A related but somewhat simpler possibility is that working is easier than starting: people are bad at scheduling and while late-night writing is no different than morning writing and just as effective in theory, people tend to choose to fill up their schedules, and repeatedly ‘accidentally’ find themselves with too little time to write at night; every hour of evening writing that people do get done is just as effective as morning hours, but there are fewer such hours. Doing it in the morning is then simply a little trick to make sure that other obligations/excuses literally cannot come first.

Another possibility is that the day really does use up some sort of ‘willpower’ or ‘creativity’: all the little things one does before the writing late in evening fill up one’s mind. There is nothing special about morning hours, they merely happen to be the conscious hours closest in time to sleep pushing the big reset button on the brain. If someone slept during the day & woke up at midnight, that person would then be best off writing at midnight, right after waking up, rather than 8 hours later in the morning, equivalent to their afternoon. (Tononi’s SHY theory of sleep would be a low-level neurobiological explanation along these lines.) These sorts of theories have a problem with the existence of authors who prefer to work at the end of their (subjective) day and are energized at night—why are they not just immune to what should be generic effects of biology/psychology, but positively energized?

A version of this ‘thing building up/wearing out over the day’ is that it is related to ego depletion or ‘decision fatigue’4 or opportunity cost, where the increasing number of accomplished activities it becomes an excuse to write less—“I had a busy day, I can take it easy tonight.”—or one has difficulty truly focusing because there are so many other things which one could do (Kurzban’s opportunity cost model).

Yet another version might be that sleep itself is the key: sleep, aside from any resetting, is also responsible for memory formation and appears involved in unconscious processes of creativity.

Sleep is a long time period in between phases of working, allowing for the incubation effect5 to operate, and the incubation effect may be particularly benefited by sleep. So, one wakes up primed to work on the next piece of writing (that one has likely been mulling a long time), and by instead puttering around making tea or breakfast, one dissipates the potential. In this model, instead of one’s writing potential gradually deteriorating over the course of the day as the mind fills up/willpower is used up, it falls sharply and then hits a baseline and perhaps follows the usual circadian rhythms thereafter with a nadir at siesta time etc.

Or, perhaps there is something special about the liminal half-sleep state, which makes fantasizing or imaging easier. One parallel we might draw is with the ancient connection between fiction writers and alcohol: writers are notorious for drinking, often to excess. Is there something about the depressant or loosening of inhibitions of alcohol which assists writing, which might also be reproduced in the morning? On the other hand, nonfiction writers like journalists or philosophers or scientists tend to be associated with stimulants, particularly nicotine, caffeine, and amphetamines (not to mention modafinil)6; while those, particularly amphetamines, are less associated with fiction writers.7 (This makes me wonder if there is a connection to another anomalous anecdotal phenomenon, the so-called alcohol “afterglow” effect, and if my poor LSD microdosing results reflect my own nonfiction tendencies.)

This half-asleep explanation neatly explains why evening doesn’t work. It wouldn’t apply to falling asleep as there is an asymmetry: a half-asleep person in the morning who is writing is getting gradually more alert and spending the rest of the day awake, and can build on whatever mental seeds were planted; while a half-asleep person in the evening would frustrate sleep by trying to write, can’t write for long before falling asleep, and when they do fall asleep, would forget the preceding ~10 minutes.

In reading through the several hundred Goodreads interviews, I have been struck by the extent to which morning fiction authors (but much less so nonfiction authors), while praising the benefits of routine & sitzfleisch in simply getting writing done at all, repeatedly invoke language involving altered states of consciousness, describing the benefit of the morning (especially early morning) as enabling reveries/daydreams/trances/fantasies/dream-like states where they can go through a ‘portal’ and be absorbed into their fictional world for several hours without interruption, with the effect wearing off before noon (consistent with the circadian rhythm & the late-morning peak), and later in the day being reserved for planning/world-building/review/editing and more quotidian tasks—and, complementarily, how evening writers seem to tilt towards nonfiction but, in an exception which proves the rule, sometimes use similar language for their writing in late evening, like past midnight to dawn.

I am reminded of nothing so much as Stephen LaBerge’s lucid dream method Wake Initiated Lucid Dreams (WILD), which also involves getting up early in the morning, being wakeful for a short time, and then attempting to enter an altered state of consciousness (sleep) where one can experience & control an unfolding narrative (lucid dream). This raises some interesting possible connections: would fiction writers benefit from use of dissociative or psychedelic drugs in the morning? (Alcohol comes to mind. And I met a woman once who told me her best fiction, with the most vivid images, was always written after taking 4g of psilocybin mushrooms.) Do any of the lucid dream methods (eg. LaBerge finds that galantamine drug use greatly increases lucidity odds) transfer to fiction writing?

In this paradigm, nonfiction authors do not particularly benefit from morning writing aside from the benefits of having a regular habit, because their work is much less heavy on inspiration: they do not need to bang out thousands of words in a trance to make the fiction come to life, but are piecing together their research, with a much smaller ratio of inspiration:words. The necessary inspiration can happen at any time, while most of their time is spent doing the background research; their subconscious can mull over all the notes at leisure (incubation effect) and the final results written down whenever. Fiction authors can substitute the morning with evening use of alcohol or sleep deprivation or binging to maintain the flow (or, like Maya Angelou, combine all four by drinking in the morning while getting up extremely early to write in periodic book-writing binges).

Or, perhaps it is a lack of sleep: sleep deprivation can cause odd mental states including mania and loss of inhibitions, and there is a peculiar but seemingly real phenomenon where acute sleep deprivation in people with major depressive disorder substantially temporarily relieves their symptoms (“Meta-Analysis of the Antidepressant Effects of Acute Sleep Deprivation”, et al 2017).

Many writers are melancholic, so early mornings, especially cross-chronotype, might be an inadvertent rediscovery of this to the extent that they shortchange sleep in order to get up. Perhaps most people are not in the throes of full MDD, but there might be a more mild effect. If the sleep-deprivation effect is the culprit, then writers who do this need to be cutting sleep considerably and the effects will be only temporary, since chronic sleep deprivation doesn’t help (and worsens cognition); this might also explain anecdotes where the person maintains that morning-writing works for them but they could only do it for a few days or once in a while—naturally, the more sleep deprivation the harder it is to get up, and as both the sleep deficit builds up & the anti-depressant effect disappears, they will find morning-writing increasingly useless and will stop. This might seem like an undesirable hypothesis but it still allows occasional benefits on carefully-chosen occasions, such as finishing or starting a novel.

There is also the possibility that these patterns reflect mental illness; not schizophrenia (which is blighting), but mood disorders. Particularly striking are 1987 & 1989.

Directions

There are a few things one could do to generate a little more data on this:

systematically go through the Paris Review interviews and the similar GoodReads interviews to note down all cases where an author is asked about writing time, rather than a few examples; this avoids the risk that morning writing advocates have selectively chosen examples from the interviews. As the writers are not chosen for their writing habits and the interview question are fairly formulaic, presumably the interview series could be considered a quasi-random survey sample of successful authors.

run a population-sample survey (I have done one USA survey myself but more extensive surveys & surveys elsewhere would be useful)

run surveys in more elite-writer samples

run a (non-blinded) self-experiment: create a list of things to systematically work on; flip a coin to decide whether to get up early, record total words-written+time-spent etc. (I can’t decide if I would be biased towards wanting it to work or wanting it to fail: of course I want to be better at writing, but on the other hand, I really hate waking up early—surely there’s some easier way!)

Research

1986, “Writing method and productivity of science and engineering faculty”: to go into more detail, it reports:

The respondents tended to schedule their work between 8AM and 8PM, with the morning hours being the most common time of day (Table 3). Positive but non-statistically-significant correlations were obtained for these time intervals. Night owls were rare and not unique in their productivity. In terms of the duration of writing sessions, the data indicate a preference for one to three hours. Working for 1 to 2 hours was statistically-significantly correlated with productivity. But as will be explained later in describing the multiple regression analyses, this effect is best attributed to other factors correlated with the frequency of working for 1 to 2 hours. Highly regular work scheduling was not the rule; the most common response was only a 3 on the 7 point scale. “Write in spurts” and “marathon writing just before a deadline” were comments listed by respondents that match the pattern commonly observed in Boice and Johnson’s (op. cit.) survey. As in Boice and Johnson’s study, regular writing was positively correlated with productivity, but here the relationship was weak and non-statistically-significant.

Survey Item

Mean

Mode

Std. Dev.

Productivity Correlation (r)

Midnight–4AM (hour of day)

1.76

1.00

1.29

0.01

4AM–8AM

1.87

1.00

1.49

0.04

8AM–Noon

4.61

6.00

1.44

0.17

Noon–4PM

4.34

4.00

1.33

0.15

4PM–8PM

3.60

4.00

1.54

0.13

8PM–Midnight

3.80

2.00

1.80

0.05

0–1 hour (Duration)

3.50

2.0

1.58

0.09

1–2 hours

4.46

6.0

1.40

0.22*

2–3 hours

4.44

6.0

1.36

0.07

3–4 hours

3.49

4.0

1.63

-0.04

More than 4 hours

2.76

1.0

1.73

-0.12

Every working day (regularity)

3.01

3.0

1.50

0.11

Table 3: Analysis of Work Scheduling (n = 121; The response scale ranged from “Never” (1) to “Always” (7). * = p < 0.05)

Another interesting aspect of 1986 is that almost all variables correlate non-statistically-significantly with “productivity” (defined in Kellogg as the total number of books/papers/reports/grant-applications/grant-reports written in the previous 3 years), and most are of small magnitude. Measurement error & range restriction come to mind as biasing effects towards zero, but it’s still consistent with my own experience that it is difficult to find anything which strongly correlates with ‘productivity’, much less causes it.

1989, “The psychologist as wordsmith: a questionnaire study of the writing strategies of productive British psychologists”, conduct a similar survey as Kellogg but do not give any statistical details that I can find, saying merely

In the present study most of our productive psychologists had no real preference for any time of day at which to work. The morning appeared to be slightly preferred to the afternoon and the afternoon slightly preferred to the evening. Regular working times were correlated with overall productivity, but productive book writers wrote sporadically (in term time). These findings were very similar to those of 1986 who showed that the majority of his 121 engineers worked in the morning, and then the afternoon, but that a highly regular work schedule was not the rule.

1997, “Which is more Productive, Writing in Binge Patterns of Creative Illness or in Moderation?”

1997 summarizes a subset of several of his earlier publications, focusing on writing in rare long bursts (“binging”) or in smaller frequent sessions: he observed for 2 years 16 newly-hired postgraduates while they worked on research writing at regularly scheduled times (apparently no fiction writers were included in this particular sample), dividing them into 8 “binge” & 8 regular writers. He observed that the regulars wrote ~12 days/month vs ~2, 12 pages/month vs <2, and published >1 manuscript vs <1.

Rescue2018, “Productivity in 2017: What we learned from analyzing 225 million hours of work time”; analytics over hundreds of thousands of users:

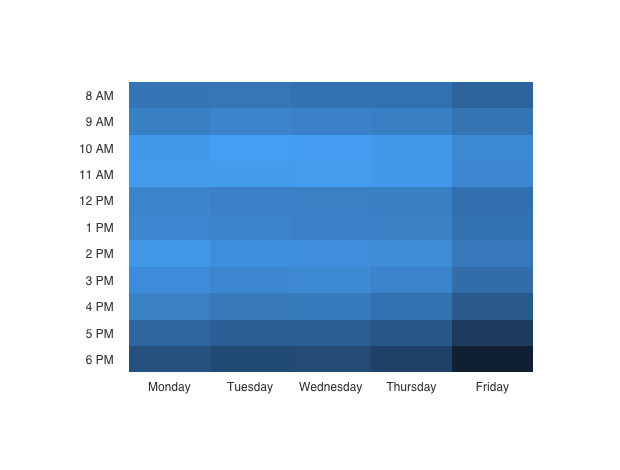

Looking at the time spent in software development tools, our data paints a picture of a workday that doesn’t get going until the late morning and peaks between 2–6pm daily…While writers are more likely to be early birds…Writing apps were used more evenly throughout each day with the most productive writing time happening on Tuesdays at 10AM.

“Time spent in writing tools (light blue)”: RescueTime analysis of distributing of writing app use over time of day over the week: note intense band 10–11AM every day

Allowing for the different time buckets, the RescueTime results closely parallel 1986’s survey responses. Aside from being an enormous data sample, RescueTime notes an interesting contrast: despite being apparently similar activities (both mostly involve slinging text), the temporal timing of software development & writing are strikingly different. Thinking back, I don’t recall early-morning programming being a trend among programmers (programmers are infamous for preferring to come in late and late-night programming sessions which may wrap around the clock, especially in college—though the original reason, that “the computers are less busy at night”, has long since expired). It’s fascinating that the stereotypes about writing vs programming line up so well with the RescueTime data.

2018 Google Surveys, general USA population sample, asking self-identified writers/researchers/scientists their chronotype & ideal writing time, Gwern:

I ran this survey in October 2018, using Google Surveys, asking a question akin to 1986’s survey, like “if you are a professional writer, blogger, researcher, or scientist do you find you write best at: [not a writer]/[Midnight–4AM]/[4–8AM]/etc?” At $0.10 a response, if 5% of the population could be considered some sort of writer (which sounds reasonable to me) and we want another n = 121 to equal 1986’s sample size, the survey would only cost 0.10 × 20 × 121 = $316.86$2422018. A second question could be added to ask if the respondent considers themselves more of a morning or evening person, however, it dectuples the cost; as in my catnip surveys, it should be possible to combine the questions into a single question which can hopefully provide a useful datapoint. (GS tries for a representative population sample by techniques like reweighting; I don’t know if they take time-of-day into account and thus lark/owl type, but the surveys typically run over several days so hopefully they wind up being inherently balanced anyway.)

If morning is the most common (replicating the 1986 & RescueTime results), and if many evening-preferring respondents still answer that mornings work better for writing, that would be pretty good evidence for morning writing being a real phenomenon (although still leaving the causal status ambiguous and not answering the question of whether owls—like me—would benefit from switching to morning writing).

On 2018-10-27, I launched an all-ages all-gender USA population survey on Google Surveys. Because of the need to run as a 1-question survey, I condensed the two questions into one and simplified it considerably into just morning/evening preference and morning/evening self-estimated writing performance, giving 5 possible responses (1+2x2=5). As most respondents will be useless—I guesstimate 5% would consider them professional writers of some sort, so for a few hundred responses, I need 20x as many; I settled on n = 5000/$654.68$5002018 for the survey, which should deliver a precise enough result. The question looked as follows:

If you are a writer/researcher/scientist, are you a morning/evening person & when do you write best? [answers displayed either ascending or descending at random]

I don’t write or blog

Morning person; best writing during morning

Morning person; best writing during evening

Evening person; best writing during morning

Evening person; best writing during evening

The survey finished 2018-10-29 with the following results (percentage is population-weighted out of equivalent n = 3,999; n is raw counts out of the n = 5004 actually collected; CSV)

70% (3515)

9.9% (467)

4.0% (196)

4.0% (193)

12.1% (633)

The percentage of people willing to claim to be writers was ~6x larger than I expected, which is troubling (do really that many people write?). Otherwise, the responses appear reasonably evenly balanced: 663 morning people vs 826 evening people. The percentage of overall counter-chronotype self-rated writing performance is 26%. On average, 55% of respondents thought evening-writing was best. The key question, of course, is whether morning-writing is more preferred for counter-chronotype writing: there is a slight preference here, but it is the opposite of predicted, with 29% of morning people believing they write best in evening versus 23% of evening people saying morning is best for them. (The difference is statistically-significant at p = 0.008/P ≈ 1.8)

This does not strongly endorse morning-writing, although it is surprising how many people think they write best counter-chronotype. Of course, the fact that fewer people believe they write better in the morning rather than evening doesn’t prove morning-writing isn’t a thing: one possibility is that people simply haven’t given it a fair try, or that it only works for professional writers at a high level, or that it is heterogeneous and there is a small fraction of people for whom morning-writing works really well (and so everyone should give it a try just in case). The overall even split of chronotype does give a baseline expectation for elite writers, though.

2019 Google Surveys, general USA population sample, asking self-identified published writers writing time, Gwern:

Compiling the anecdotes from Goodreads & The Paris Review, I noticed what seemed like a trend towards fiction writers emphasizing the morning as the best time to write, and avoiding afternoons/evenings except as continuations of morning writing or noting that afternoons/evenings were useful for secondary tasks (review/editing/background research/correspondence), while nonfiction writers can write at any time. If there is a genre split, this would explain why the anecdotes are polarized but the RescueTime/Twitter/GS general surveys show balance: the nonfiction writers are masking the fiction writers when aggregated, and since these surveys do not split responses by type of writing (and 1986/1989 presumably exclude fiction writers entirely by surveying STEM or psychology faculty only), no analysis can reveal this heterogeneity. There were too few nonfiction authors in the anecdote compilation to allow easy formal statistical modeling, but this does generate a testable hypothesis: if I run new surveys which do collect nonfiction vs fiction covariates, there should be a distinct difference in morning vs evening writing preference.

As before, a 1-question forced-choice survey is most cost-effective, so I do another 5-way split between nonfiction/fiction/morning/afternoon–evening. One adjustment I make is to rephrase it in terms of ‘afternoon–evening’ since based on the anecdotes since, it’s become clear that writing in the evening is unusual and afternoon–evening is more common.

If you are a published writer of fiction or nonfiction, when do you write best?

Nonfiction; morning

Nonfiction; afternoon–evening

Fiction; morning

Fiction; afternoon–evening

I’m not a writer/NA

The morning/fiction correlate feels large, possibly a doubling of the baseline 1:1 odds, so a quick power analysis suggests a total n = 120 of responders (

power.prop.test(p1 =2/4, p2 = 3/4, power=0.80)), and since 30% of the first survey respondents provided a writer response, n = 120 writers requires a total sample size of n = 400. I’m suspicious that <30% will respond or that the effect will be so big underneath the measurement error and thus that n = 400 is a loose lower bound at best, so I doubled it to n = 800.I launched the survey on 2019-07-20, random reversed order, n = 800 ($80). Response rates turned out to be lower and imbalanced towards nonfiction responses, so I doubled the sample with additional surveys, combined with coupons. The final n = 2103 with n = 462 (22%) useful writer responses (CSV). Breakdown:

Fiction:

“Fiction; afternoon–evening”: 76

“Fiction; morning”: 95 (55%)

Nonfiction:

“Nonfiction; afternoon–evening”: 87

“Nonfiction; morning”: 204 (70%)

The result was the opposite of predicted, with nonfiction writers more likely to respond with morning preference (P ≈ 1):

df <- data.frame(Morning=c(95,204), Fiction=c(TRUE,FALSE), N=c(171,291)) df # Morning Fiction N # 1 95 TRUE 171 # 2 204 FALSE 291 prop.test(df$Morning, df$N) # # 2-sample test for equality of proportions with continuity correction # # data: df$Morning out of df$N # X-squared = 9.355829, df = 1, p-value = 0.00222277 # alternative hypothesis: two.sided # 95 percent confidence interval: # -0.2412962960 -0.0496544486 # sample estimates: # prop 1 prop 2 # 0.555555556 0.701030928 library(brms) brm(Morning|trials(N) ~ Fiction, family=binomial, data=df) # ...Population-Level Effects: # Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Eff.Sample Rhat # Intercept 0.86 0.12 0.62 1.11 4307 1.00 # FictionTRUE -0.63 0.20 -1.03 -0.24 3244 1.00

Table

Author |

Date |

Type |

Time |

Hours |

Source |

Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1986 |

Nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8AM–12PM, 12PM–4PM |

1986 survey |

Top 2 time-ranges; ordinal scale mean ratings >4 for those buckets, others, like 4AM–8AM, can be half or less. |

|

2018 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning |

10AM–11AM |

RescueTime blog analytics |

This is the peak writing time; aggregate writing times span the clock. |

|

2018 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Evening |

? |

Google Surveys |

On average, respondents thought they wrote best at evening; survey respondents were more likely to prefer evening when writing counter-chronotype. |

|

2019 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Google Surveys |

n = 95 |

|

Gwern Google Surveys |

2019 |

Fiction |

Afternoon–evening |

? |

Google Surveys |

n = 76 |

Gwern Google Surveys |

2019 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

? |

Google Surveys |

n = 204 |

Gwern Google Surveys |

2019 |

Nonfiction |

Afternoon–evening |

? |

Google Surveys |

n = 87 |

Anecdotes

Table

Author |

Date |

Type |

Time |

Hours |

Source |

Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9AM–10:30AM |

The Guardian interview |

||

2017 |

Fiction |

Morning |

4AM–12PM |

The New York Times interview |

||

2017 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

10AM–1PM |

The New York Times interview |

||

1964 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

10AM–12PM, 6–7PM |

Playboy interview |

||

? |

Nonfiction |

Morning–evening |

9AM–6PM |

Biography |

Campbell refers to “reading” in this anecdote of his youth; unclear if that includes writing or if he changed later. |

|

? |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–2PM |

Biography |

||

? |

Fiction |

Afternoon–evening |

1PM?–3AM |

Biography |

||

? |

Nonfiction |

Morning–evening |

11AM–1PM, 11PM–2AM |

Biography |

||

1969 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

5AM–7AM, 5PM–1AM |

McNelly interview |

||

1968 |

Fiction |

Afternoon |

12:30PM–5PM |

McNelly interview |

||

2015 |

Fiction |

Morning |

6AM–10AM |

Goodreads |

||

2017 |

Fiction |

Morning |

4AM–7AM |

Goodreads |

Inferring times from his preference to write “before the light gets up in the sky…before the rest of the city wakes up…dark morning hours” |

|

2016 |

Fiction |

Evening |

8PM–12PM |

Goodreads |

||

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8AM–12PM |

Goodreads |

||

2014 |

Fiction |

Evening |

?PM–4AM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Evening |

12PM–4PM, 4PM–3AM |

FAQ, online interview |

||

1990 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

10AM–4PM |

Paris Review |

Her later GoodReads interview suggests she loosened her schedule after her daughter grew up. |

|

1947 |

Fiction |

Evening |

11PM–8AM |

Biography |

||

2004 |

Fiction |

Evening |

?PM–?AM |

Interview anthology |

||

1986 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

?AM–?PM |

Paris Review interview |

Inferred from his description 8-hour days which terminate before “the evening”, reserved for research. |

|

2018 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

5AM–?PM |

Paris Review interview |

||

? |

Nonfiction |

Evening |

12AM?–6AM? |

Biography |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning |

1AM–?AM |

Paris Review |

||

1954 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9AM–? |

Paris Review interview |

“He rose, he said, early, and was always at his desk by nine.” |

|

1988 |

Fiction |

Morning |

7:15AM–12PM |

Polish interview |

Based on her “ideal schedule”: “7:15 a.m.—get to work writing, writing, writing. / Noon—lunch.” |

|

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–?PM |

Paris Review interview |

Schedule varies in how late Gibson goes into the afternoon/evening, but assuming his Pilates classes are 1 hour, he doesn’t start before ~9AM. |

|

2002 |

Fiction |

Morning |

4AM–? |

2002 Locus interview |

||

2018 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

7AM?-1PM, 7PM-?PM |

Goodreads |

Writing starts after “kids are off to school” (which for Americans would generally be 7–9AM depending on age), and resumes in “the evening” (presumably after a family dinner) |

|

2018 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–evening |

?AM-?PM |

Goodreads |

Harkness describes writing for the first hour every day as a “warm-up…the rest of the day kind of clicks along”. |

|

2018 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

7AM?–?PM |

Goodreads |

Like Williams, writing is done in between children going to school & returning. |

|

2018 |

Fiction |

Afternoon–evening |

Noon?–3AM? |

Goodreads |

“I bitterly lament the loss of my former schedule. [Laughs] I would go to sleep at 3 a.m. and wake up at 11, and that was so nice.” |

|

2019 |

Nonfiction |

Morning–evening |

8AM?–1AM? |

New York Times profile |

||

2018 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–noon |

Goodreads |

||

2018 |

Fiction |

Any |

Any |

Goodreads |

||

2017 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9:30AM–3PM |

Goodreads |

||

2017 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

7AM?–?PM |

Goodreads |

During school hours. |

|

2018 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

Previously during school hours. |

|

2018 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–1PM? |

Goodreads |

Genova writes for 4 hours regularly at Starbucks; that suggests starting around 9AM and finishing around 1PM. |

|

1933 |

Fiction |

Afternoon |

1PM–4PM? |

The Name And Nature Of Poetry |

“Having drunk a pint of beer at luncheon…I would go out for a walk of two or three hours” |

|

<1952 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Attributed by 1952 |

“John Peale Bishop recommended going as soon as possible from sleep to the writing desk.” |

|

2017 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

? |

Goodreads |

Hamid preferred “late at night…a vampire-like existence” but due to children now follows “completely different” school-hours. |

|

2016 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

10AM–3PM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Evening |

10PM–4AM |

Goodreads |

||

2016 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2016 |

Fiction |

Morning |

7:30AM–3:00PM |

Goodreads |

||

2016 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2016 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

9:30AM–8PM |

Goodreads |

||

2016 |

? |

Morning |

5AM–noon |

Goodreads |

As described by Julian Fellowes |

|

2016 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9AM?–noon |

Goodreads |

“…Most people write from whenever they wake up until noon or one. That’s your writing period. I do it every day…during that period of three or four hours.” |

|

2016 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9:30AM–12:30PM |

Goodreads |

||

1990 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–evening |

?AM–noon, 4:30PM–8PM |

Paris Review |

||

2015 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?–noon? |

Goodreads |

“I work many hours a day, usually starting in the morning. I’m much better then than in the afternoon or the evening.” |

|

2016 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2015 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM?–5PM? |

Goodreads |

“I’m used to just getting up, coming downstairs, sitting at my desk and writing. Sometimes if the writing’s going really well I can write almost all day and all night but usually it’s a pretty normal day, not quite 9 to 5 but not that far off.” |

|

2016 |

Fiction |

Evening? |

? |

Goodreads |

“It changes from book to book. With these stories, I think I was up very late at night, writing, like, at 2 a.m. And then I’d just sleep a lot and wake up and write some more. But with other books, I’ve had much more structure.” |

|

2019 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

8AM–4AM? |

Glamour profile |

“To pull it off, she works 20 to 22 hours a day…She gets to her office—down the hall from her bedroom—by 8:00 A.M…‘If I have four hours [of sleep], it’s really a good night for me’”. May be a ‘short sleeper’. |

|

2015 |

Fiction |

Morning |

4:30AM–10AM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

4:30AM–noon |

Goodreads |

||

2015 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon? |

? |

Goodreads |

Multiple schedules reported: 5AM–8AM? (before day job), 10AM–3PM (full-time writer), then miscellaneous (while childrearing). |

|

2015 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–noon |

Goodreads |

After walk/breakfast/shower, until noon. |

|

2015 |

Fiction |

Evening? |

?PM–4AM |

Goodreads |

Pamuk thanks “coffee and tea” and says “especially before my daughter was born I used to write until four in the morning.”, suggesting starting only in the evening. |

|

2015 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2015 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2014 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

“when I have child-free time” |

|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8AM?–noon, 3PM–7PM |

Goodreads |

8 hours total, morning until noon (=8AM), afternoon until 7–8PM (=3–4PM) |

|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM?–4PM? |

Goodreads |

“I…write at the kitchen table when the kids are at school.” |

|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–4:30PM |

Goodreads |

||

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

6AM–?AM,?AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

Winspear gives a detailed idealized schedule: she wakes ~5:30AM, writes for several hours, walks/breakfasts, writes additional hours, exercises, writes additional hours, and stops sometime before dinner. |

|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8:30AM–noon, ?PM–6PM |

Goodreads |

||

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning, afternoon, evening |

11AM–noon, 1PM?–2PM?, midnight–4AM |

Goodreads |

Gabaldon writes briefly during the day, then wakes up at midnight to do her main writing. |

|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9AM–11AM |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM?–?PM |

Goodreads |

Originally a more typical 8AM–11:30AM. |

|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

“I need to write first thing in the morning…I’m at the computer anywhere from four to six hours.” |

|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9AM?–noon? |

Goodreads |

“Once my kids have gone to school, I…just switch off for three hours.” |

|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8AM–noon |

Goodreads |

||

2014 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

“But I write all day long.” |

|

2014 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning, evening |

?PM-?AM |

Goodreads |

Both late night & early morning: “I like to write late at night when everything is really quiet—especially here in New York—and I’ll work right through until the morning. But if I’m home in Sierra Leone, it’s different, and I usually write early in the morning or when I can” |

|

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

?AM–3PM? |

Goodreads |

Starts in the morning after meditation, then “Usually I write until mid-afternoon”. |

|

2017 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2013 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

“I wake up in the morning, and the first thing I do is go to my favorite café.” |

|

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

? |

Goodreads |

“I only write in the daytime—never at night.” |

|

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

?AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

“On a perfect day I walk the dogs, get a cup of coffee, and go over there and just stay for seven or eight hours.” |

|

2013 |

Fiction |

Afternoon |

1?PM–4?PM |

Goodreads |

“I sit down in the afternoon to write generally. I don’t write more than two, three hours at a time.” |

|

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8AM–noon |

Goodreads |

||

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2013 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

“When the writing is going well, I’m obsessive—I roll out of bed and go to work.” |

|

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning |

5AM–8AM? |

Goodreads |

“…waking up at about five o’clock in the morning…I have a couple of hours before any of my kids have woken up, and that’s what I call the ‘Dream Time’.” |

|

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning |

6AM–noon |

Goodreads |

||

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9:30AM–2PM |

Goodreads |

||

2013 |

Fiction |

Evening |

?PM–5AM |

Goodreads |

||

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

?AM–7:30PM |

Goodreads |

Multiple stints. |

|

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

10:30AM–5PM |

Goodreads |

||

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

6AM–7PM |

Goodreads |

||

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–2PM |

Goodreads |

||

2013 |

Fiction |

Morning |

7:30AM–12:30PM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning |

4:30AM–10AM? |

Goodreads |

Writes for 4 hours, takes a break for breakfast, then edits, apparently stopping before lunch. |

|

2012 |

Fiction |

Any |

Goodreads |

|||

2016 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

10AM–3PM |

Goodreads |

Inferred from childcare description. |

|

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–noon |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–evening |

?AM–7PM |

Goodreads |

“after breakfast…until 7 o’clock” |

|

2011 |

Fiction |

Evening |

7PM–3:30AM |

Personal website |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

9AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning, evening |

?AM–?PM? |

Goodreads |

“I always start out my writing day with a strong cup of black coffee and find that my writing flows more the first thing in the morning (after I get my children off to school) or very late at night.” |

|

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–5PM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–5PM |

Goodreads |

Same interview as Stephen Baxter, “It’s pretty much like that for me.” |

|

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8:30AM–1PM, 3:15PM–5PM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9AM–12:30PM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening? |

?AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

“When I get up, I read the paper at the kitchen counter…then I go up to the office…and I stand in front of the desk 12 hours a day.” |

|

2012 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning? |

9AM?–? |

Goodreads |

Lamott seems to imply she starts at 9AM in discussing the importance of routine. |

|

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning |

5AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

||

2012 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon? |

9AM?–?PM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Afternoon? |

?PM–5PM |

Goodreads |

Roth is facetious about trying & failing to write in the morning, so perhaps she writes in the morning as well. |

|

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–2PM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

7AM–11AM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Any |

any |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–3PM? |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning |

4AM–? |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM |

Goodreads |

||

2008 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2008 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Afternoon? |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2008 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8AM–4PM |

Goodreads |

||

2008 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2008 |

Nonfiction |

Morning? |

? |

Goodreads |

Walker appears to have been both: “I’m definitely not an up-all-night kind of writer, though I used to be. Now I’m more of an early riser.” |

|

2008 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–noon |

Goodreads |

“breakfast till lunch” |

|

2008 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning?–afternoon? |

?-3PM? |

Goodreads |

“my gym has a coffee room with two cubicles. I go there, write, work out and take the bus home mid-afternoon.” |

|

2008 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon? |

?AM–11AM, ?PM–?PM |

Goodreads |

Stephenson writes in the morning as usual but also “Then I go exercise and spend the afternoon working on something completely unrelated.”—more fiction writing, or one of his many non-writing projects? |

|

2008 |

Nonfiction |

Morning–evening |

?AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

||

2008 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

?AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

“Best time is late morning or early afternoon.” |

|

2008 |

Fiction |

Morning, evening |

? |

Goodreads |

“I usually write in the morning or very late at night” |

|

2008 |

Nonfiction |

Morning? |

5AM–7AM? |

Goodreads |

Grogan wrote 5AM–7AM for his first book before his journalist job, but quit & switched to an unspecified schedule afterwards. |

|

2008 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

?AM–noon |

Goodreads |

“I might write for a couple of hours, and then I head out to have lunch and read the paper. Then I write for a little bit longer if I can” |

|

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8:30AM–1PM |

Goodreads |

||

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8:30AM–1PM |

Goodreads |

Binchy interview. |

|

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–?AM |

Goodreads |

||

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

Simmons describes “wonderfully wasted” mornings with slow breakfasts but still seems to start before the afternoon. |

|

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning? |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning, evening |

8AM–1PM, ?PM–?PM |

Goodreads, NYRB, Paris Review |

Oates writes before breakfast, and on good days, eats only at 2–3PM. |

|

2009 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning |

10AM–noon |

Goodreads |

Not quite a pure morning writing: “although I sometimes write later in the afternoon and in the evening.” |

|

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

9AM–6PM |

Goodreads |

Originally 5AM–7PM before job; increasingly later. |

|

2009 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9AM–11AM? |

Goodreads |

“I begin to write in earnest around 9…Sometimes I can get that [1000 words] done in 2 hours; sometimes it takes all day.” |

|

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning |

4:45AM–?AM |

Goodreads |

||

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2009 |

Fiction |

Evening |

? |

Goodreads |

Wells gives several schedules over the years, but her current one seems quite late, possibly starting at midnight. |

|

2009 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon? |

?AM |

Goodreads |

||

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM-?PM |

Goodreads |

“I get up very early in the morning…I work every day for a long period of hours, drinking lots of coffee…” |

|

2009 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–5PM |

Goodreads |

||

2009 |

Fiction |

Evening |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2009 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

4AM–7:30AM |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon |

7AM–3PM? |

Goodreads |

“By mid-afternoon I’m sort of spent.” |

|

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning |

6AM–10:30AM |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning |

5AM–8AM |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

?AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon? |

10AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

Quindlen doesn’t specify an end-time but as a prolific author only starting at 10AM, she presumably must go into the afternoon. |

|

2010 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning |

6AM–noon |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Afternoon–evening |

?PM–?PM |

Goodreads |

“then in the afternoon I have the pleasure of writing. If I am trying to get through a scene or get on with the novel, then I reread and write again at night.” |

|

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning |

5AM–noon |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8AM?–?PM |

Goodreads |

After kids leave for school, a 1.5 hour delay to get into the mindset, then she’s “good for 2,000 words”, so perhaps to noon? |

|

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

7AM–5PM |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon, evening |

10:30AM–1:30PM, 8PM–9:30PM |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9:30AM–4:30PM |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning?–afternoon? |

?AM–?PM? |

Goodreads |

“I do most of my own writing when I’m shuttling between meetings on the subway”, which suggests during the working day. |

|

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning, evening |

9AM?–3PM?, 10PM–12PM? |

Goodreads |

“I think I’d write at night all the time if I could do it any way I wanted, but that’s not concomitant with the demands of a house with children in it.” |

|

2010 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

5AM–10AM |

Goodreads |

||

2010 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8AM–10AM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8AM?–?AM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning |

5AM–?AM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–?AM |

Goodreads |

“now I’m back in my old Starbucks…I try to write for four hours in the morning.” |

|

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–?AM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Evening |

Midnight?–5AM? |

Goodreads |

Auel starts writing when her husband goes to bed, and she says “I often catch the sun rising.” |

|

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8AM?–3PM? |

Goodreads |

School schedule. |

|

2011 |

Fiction |

Any? |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Any? |

? |

Goodreads |

Somewhat contradictory to Elizabeth Gilbert; see excerpts. |

|

2011 |

Nonfiction |

Any? |

? |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–?AM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

8:30AM–?PM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon? |

?AM–5PM? |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning, evening |

6AM–?AM, ?PM–?PM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

?AM–3PM |

Goodreads |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning |

6AM?–noon? |

Goodreads |

“up with first light” means dawn or ~5–6AM & “6 to 8 hours is the goal”, so she presumably finishes by noon or 1PM. |

|

2008 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning, evening |

?AM–?PM, 11PM–2AM |

Paris Review |

Eco disclaims a regular schedule but admits when he can, he writes in two segments: morning, and then late evening. |

|

1999 |

Nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8:30AM–noon, 1PM?–?PM |

Paris Review |

||

2013 |

Nonfiction |

Any |

?AM–3PM, ?PM–?PM |

Paris Review |

“Then we’ll make supper, and then I’ll probably do a bit more writing in the evening.” |

|

2012 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2017 |

Nonfiction |

Afternoon |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2017 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2016 |

Nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon |

? |

Paris Review |

Caro says he skips lunch with friends while writing, gets up earlier and earlier during a chapter, and works “pretty long days”. |

|

2017 |

Nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon? |

? |

Paris Review |

Schiff implies she starts writing in the morning through to afternoon by referring to skipping lunch with friends, like Caro: “there is the problem of lunch, in which the writer’s day craters. I avoid midday commitments when I’m writing, which endears me to no one.” |

|

2010 |

Fiction |

Any? |

? |

Paris Review |

“I could never work regularly like that. I work in erratic spurts.” |

|

1991 |

Nonfiction |

Any? |

? |

Paris Review |

“There isn’t one for me. I write in desperation.” |

|

1995 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning |

?AM–noon? |

Paris Review |

“All my best work tends to be done in the morning, especially the early morning, when somehow my mind and sensibility operate much more efficiently. I read and take notes in the afternoon, then sketch the writing I want to do the next morning. The afternoon is the time for charging the battery.” |

|

1996 |

Nonfiction |

Any? |

? |

Paris Review |

“I have no routine. I hate routines. I have no fixed hours for sleeping, eating, waking, working…I’m a night person, so I tend to write later in the day rather than earlier, but I have no fixed hours” |

|

1965 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–evening |

10AM–1PM, 5PM–9PM |

Paris Review |

||

1965 |

Fiction |

Any? |

? |

Paris Review |

Simone de Beauvoir: “Genet, for example, works quite differently [than me]. He puts in about twelve hours a day for six months when he’s working on something” |

|

1969 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

Description by E.B. White |

|

2018 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2009 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

5AM–?AM |

Paris Review |

||

2014 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

6AM–? |

Paris Review |

Phillips seems to write on non-work Wednesdays but comes in at 6AM on work days; however, he “claims to require very little sleep” and probably starts around then on Wednesdays too. |

|

2013 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Any? |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2009 |

Nonfiction |

Morning, evening |

?AM–?PM, 5PM–? |

Paris Review |

First thing in morning, break, then after ‘lunch’ resumes. |

|

1993 |

Nonfiction |

Morning, evening |

12AM–1AM, 5AM–7AM |

Bjork biography |

Skinner had a biphasic schedule. |

|

2010 |

Nonfiction |

Morning–evening |

9AM–7PM |

Paris Review |

McPhee says he starts at 9AM but is “gonging around” until 5PM when he actually starts writing for 2 hours. |

|

2016 |

Nonfiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1993 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1980 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1988 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–3PM |

Paris Review |

According to Anthony Hecht. |

|

2014 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

10AM–1PM, ?PM–?PM |

Paris Review |

An additional two hours after a late afternoon lunch. |

|

2019 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning |

11–12AM |

New York Times |

||

1986 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

11AM–4PM, 8PM–12AM |

Paris Review |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Morning? |

? |

Paris Review |

Hollinghurst was a “evening-and-alcohol writer” for his first novel but turned himself into a “morning-and-caffeine writer” for all later ones, |

|

1999 |

Fiction |

Morning–? |

7:30AM–? |

Paris Review |

||

2007 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8AM–1AM |

Paris Review |

||

2014 |

Fiction |

Evening |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1954 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9AM–noon |

Paris Review |

||

1969 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

“four or five hours” in the morning |

|

1994 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8AM–11AM |

Paris Review |

Historically, mixed schedule around school & work; currently, exclusively morning. |

|

2017 |

Fiction |

afternoon–evening |

2PM–9PM |

Paris Review |

||

1996 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

7AM–3PM |

afternoon–evening |

Paris Review |

Starts ~6:45AM, then is there “at least seven or eight hours every day”. |

|

2003 |

Fiction |

Evening? |

? |

Paris Review |

Used to be “All night” but shifted to at least partly daytime. |

|

2003 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1957 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8AM–4PM |

Paris Review |

||

2019 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1987 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

?AM–?PM |

Paris Review |

||

2011 |

Fiction |

Afternoon–evening? |

?–?PM |

Paris Review |

Beattie apparently had a reputation for writing late at night, but disclaims it now. |

|

1997 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2009 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Any |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1973 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1973 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–1PM |

Paris Review |

As described by interviewer & Burgess. |

|

1978 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1984 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9:30AM–1PM |

Paris Review |

||

2002 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–noon |

Paris Review |

||

2004 |

Fiction |

Evening |

?PM–?AM |

Paris Review |

Hannah describes writing after his college teaching job when he was younger, sometimes as late as 4AM. |

|

2000 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1989 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Paris Review |

Wright says he did work in the afternoon for years, but that was not his most common pattern, instead working on things at any time of day where possible. |

|

1950 |

Fiction |

Morning |

6AM–?AM |

Paris Review |

Ascribed to Cendrars by PR. |

|

1981 |

Fiction |

Morning |

8:30AM–12:30PM |

Paris Review |

||

1994 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening? |

? |

Paris Review |

<q”>I am not an early-morning person; I don’t like to get out of bed, and so I don’t begin writing at five A.M…I write once my day has started. And I can work late into the night, also.” |

|

1992 |

Fiction |

Morning? |

?AM |

Paris Review |

“I like to get up in the morning and go to work.” |

|

1974 |

Fiction |

Morning? |

?AM |

Paris Review |

Attributed by the interviewer: “Isherwood works every morning and then usually walks to the ocean to swim.” |

|

1987 |

Fiction |

Evening |

? |

Paris Review |

“all night” and “through the night”. |

|

1992 |

Fiction |

Afternoon–evening |

3:30PM–8PM |

Paris Review |

||

2019 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

9AM–6PM |

Paris Review |

Previously, until 3PM when her children returned home. |

|

2016 |

Fiction |

Morning? |

? |

Paris Review |

Solstad implies that he doesn’t write in the afternoon by describing how on one day of his “3-1-3 system” that he gets drunk in the afternoon; on the other hand, he might be implying that he writes in the afternoon on all the other days. |

|

2007 |

Fiction |

Morning |

6AM–12PM |

Paris Review |

||

1993 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

?AM–?PM, ?PM–?PM |

Paris Review |

He works for 4 hours in the morning, breaks for run, then 3 hours in the afternoon. |

|

1988 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1984 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

?AM–2PM |

Paris Review |

||

1994 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2017 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1984 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

4 hours. |

|

1979 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Paris Review |

At evening during original printing job; morning while on grants; but any time at time of interview while a teacher. |

|

1989 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

8AM?–2PM |

Paris Review |

||

1958 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning |

6AM–noon |

Paris Review |

||

1972 |

Fiction |

Morning? |

? |

Paris Review |

||

1982 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

6AM–11AM, 4PM–7PM |

Paris Review |

||

1986 |

Fiction |

Morning |

5AM–9AM |

Paris Review |

||

1987 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon |

11AM–7PM |

Paris Review |

||

1981 |

Fiction+nonfiction |

Morning–afternoon |

9AM–2:30PM |

Paris Review |

As a journalist, wrote late at night. |

|

1987 |

Fiction |

Morning |

?AM–?AM |

Paris Review |

For 3 hours in the morning after waking. |

|

1953 |

Fiction |

Morning? |

?AM |

Paris Review |

He seems to imply regularly writing in the morning after rereading previous day’s work. |

|

1991 |

Fiction |

Morning–evening |

10AM–?PM, ?PM–7PM |

Paris Review |

Break for coffee. |

|

2002 |

Fiction |

Any |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2000 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

As described by PR: “Most mornings..Herling rose…and went to his desk to continue” |

|

2009 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

7AM–?PM |

Paris Review |

Short break for breakfast, then writing until “late afternoon” |

|

2007 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

11AM–?PM |

Paris Review |

Previously, began at 9AM. |

|

2004 |

Fiction |

Morning |

4AM–10AM |

Paris Review |

||

1983 |

Fiction |

Morning–afternoon |

?AM–12:30PM, ?PM–?PM |

Paris Review |

||

1958 |

Fiction |

Evening |

? |

Paris Review |

As summarized by Paris Review, based in part on Green’s memoir. |

|

1962 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

Miller also mentions writing midnight–dawn, or morning–afternoon, when he was younger (pre-1950s). |

|

2015 |

Fiction |

Morning |

? |

Paris Review |

||

2002 |

Fiction |

Morning |

9:30AM–? |

Paris Review |

||